Topic modeling complaints to the CFPB

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) collects consumer complaints against financial companies, as I’ve discussed in this space. In trying to meet the problems identified in these complaints, whether by the CFPB or the company itself, it’s important to understand what type of product is causing the problem. Teams work on products, and the issues across different types of financial products can vary significantly.

But the distinction between “My bank is opening up credit card applications I didn’t ask for” and “my credit card company keeps calling my house, but I haven’t missed a payment” is subtle, and the sort of thing that doesn’t lend itself to easy product classifications.

You can’t just count the number of times the term “bank” is said, or “credit card” is said and get that this is about credit cards. The first is really about the bank’s service, not the credit cards themselves. The second is really about a debt collector calling someone’s home repeatedly.

To better understand what people are talking about in these complaints, I performed a modeling technique called Latent Dirichlet Allocation.

Here’s a brief introduction to how it works.

- The words in each complaint are converted to simplified versions of the words (i.e., both “property” and “properties” become “properti”) and given unique identifier numbers.

- Numbers that appear in the same complaint documents across the entire set of complaints are grouped together into “topics”. These topics typically include words from multiple documents, and the words in a document are likely to be in multiple documents. Each word in a topic is given a weighting, indicating how “important” a word is to the topic - or how many times it is mentioned across documents in conjunction with the other words.

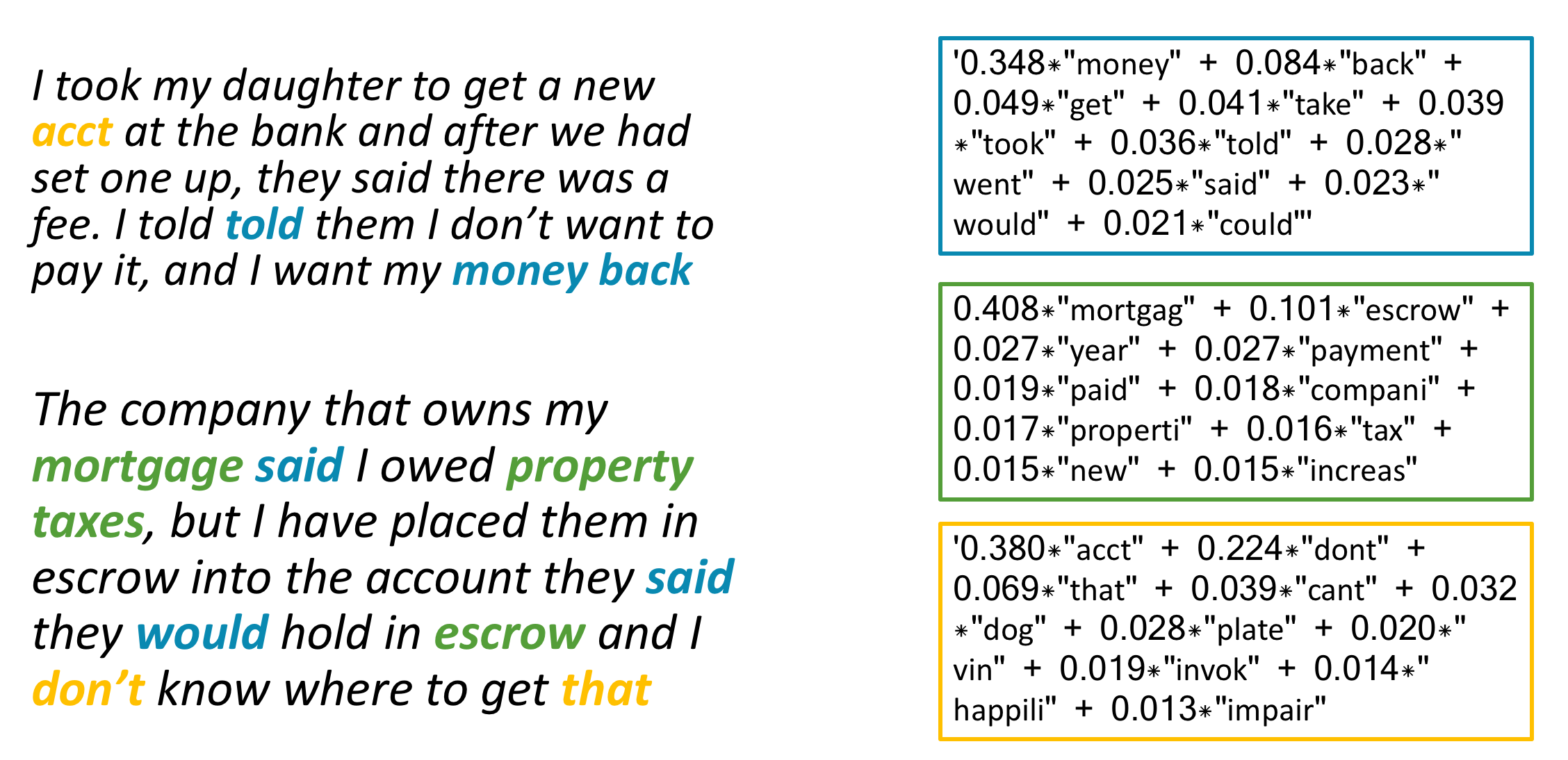

In the example below, the chart below demonstrates how words in documents on the left match up with the topics across the entire document, on the right.

The first topic is primarily about getting money back, and how consumers interact with the customer service gatekeepers who can do that. The second is all about making mortgage or other home payments (e.g., escrow, taxes). And the third is a little more opaque, with words that describe the account, and the way that interactions go. Not all topics are readily interpretable.

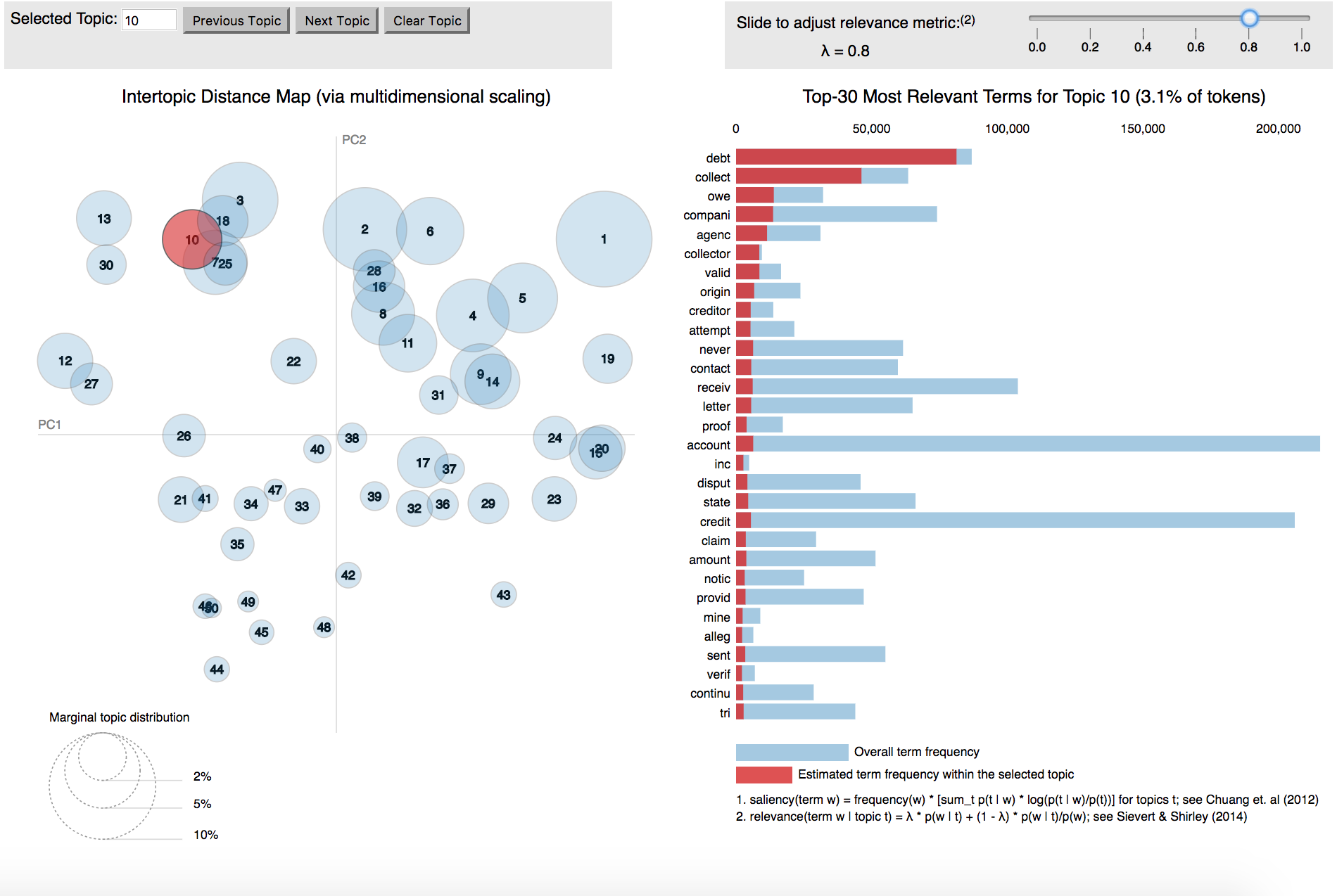

I tested out a series of the topic models to see what size might be a good descriptor, and landed on a topic size of 50. The graphic below shows the relationship between topics and the words that comprise them. Bigger circles indicate topics that are more common.

More graph details

The topics are organized by plotting them on the axes of the two linear combinations that best describe their features - a method known as Principal Component Analysis. The blue bars on the right-hand side indicate the frequency of a word across all the documents in the entire dataset. The red bar indicates how frequent the terms are within a topic. The relevance metric λ is a representation of the relative exclusivity of a term - higher values are more frequent, less exclusive, and lower values are more exclusive, but may be more idiosyncratic.The LDA visualization tool used for this project was developed by Carson Sievert and Kenny Shirley.

Click the image to see how all the topics are distributed

The topic highlighted here (just called #10), groups together words about debt collectors. The right-hand side walks includes the words that are common in each topic (the red bars) and the words frequencies across the entire dataset (blue bars).

This type of clustering is especially convenient for large datasets, where it’s impractical to read every one of the entries. Instead, you can look at the topics, and then check the distribution of those topics, especially where they are limited to certain groupings.

In the next iteration, I’ll be looking at the way these topics change depending on the companies and products that the complaints are about.